Lt Best RN, HMS Antelope

A Life in the Day of …

Lt Best RN, HMS Antelope

By the Editor – Sacrifice and duty are words easily bandied around in peacetime… perhaps Shakespeare best expressed the sentiment: “but we in it shall be remembered – We few, we happy few, we band of brothers; for he to-day that sheds his blood with me shall be my brother; be he ne’er so vile, this day shall gentle his condition; and gentlemen in England now a-bed shall think themselves accurs’d they were not here, and hold their manhoods cheap whiles any speaks that fought with us upon Saint Crispin’s day.” There is much to respect and learn from this recount of the fate of the HMS Antelope.

Darkness, absolute pitch darkness. That’s my abiding memory of what was to be, though I didn’t know it at the time, my last night Bridge watch in HMS Antelope. We had been at sea for about six weeks by this, the night of 22/23 May 1982. During that time, as well as honing our skills at escorting multiple ships in formation (we had been the sole escort for all the LSLs for most of the trip South), we had perfected our ‘darken ship’ routine. In less ‘intense’ operations – West Indies Guard Ship, Gib Guard Ship, even at Operational Sea Training – the pipe “darken ship” was met with a semi-conscientious reduction in the illumination of the Bridge instrument clusters, pulling the blackouts across the chart table and making sure the captain’s scuttle had been closed. Now though, a honed sense of the tension of being at war, combined with a healthy respect for Argentinian submarines and their capabilities, had made us zealots in the pursuit of stray light. In fact, we would have put the ARP Warden in Dad’s Army to shame. The casual flash of a torch, a casual ‘light up’ or a chink in an airlock were all absolutely taboo and drew appropriate opprobrium from all quarters.

use magazine explodes (IWM)

The other recollection, equal in my consciousness, was the silence. Apart from the gentle whir of the 1006 Radar repeater, the hum of the air conditioning and the monotonous but rhythmic click of the compass repeater tape on the Quartermaster’s console, each man had retreated, perhaps subliminally, into his own private thoughts. ‘Clubs’ on the wheel, RO Rolfe at the Tactical radio desk, Lt Jonathan Sharp (the CBO and other Officer of the Watch (OOW)) and S/Lt Marcus Batten, Officer of the Watch 2 on the chart. We had all fallen into a pattern over the past few weeks of getting on with it. Though in early days, when we were at Ascension transferring stores, or even when we had delivered our charges – the LSLs – to the theatre and returned, via South Georgia, with prisoners, a penguin, a wildlife film crew and a wanted criminal (another story), there had always been time for what Generation Z would call these days ‘bants’(banter). Now it was different. For this was the eve of battle for us.

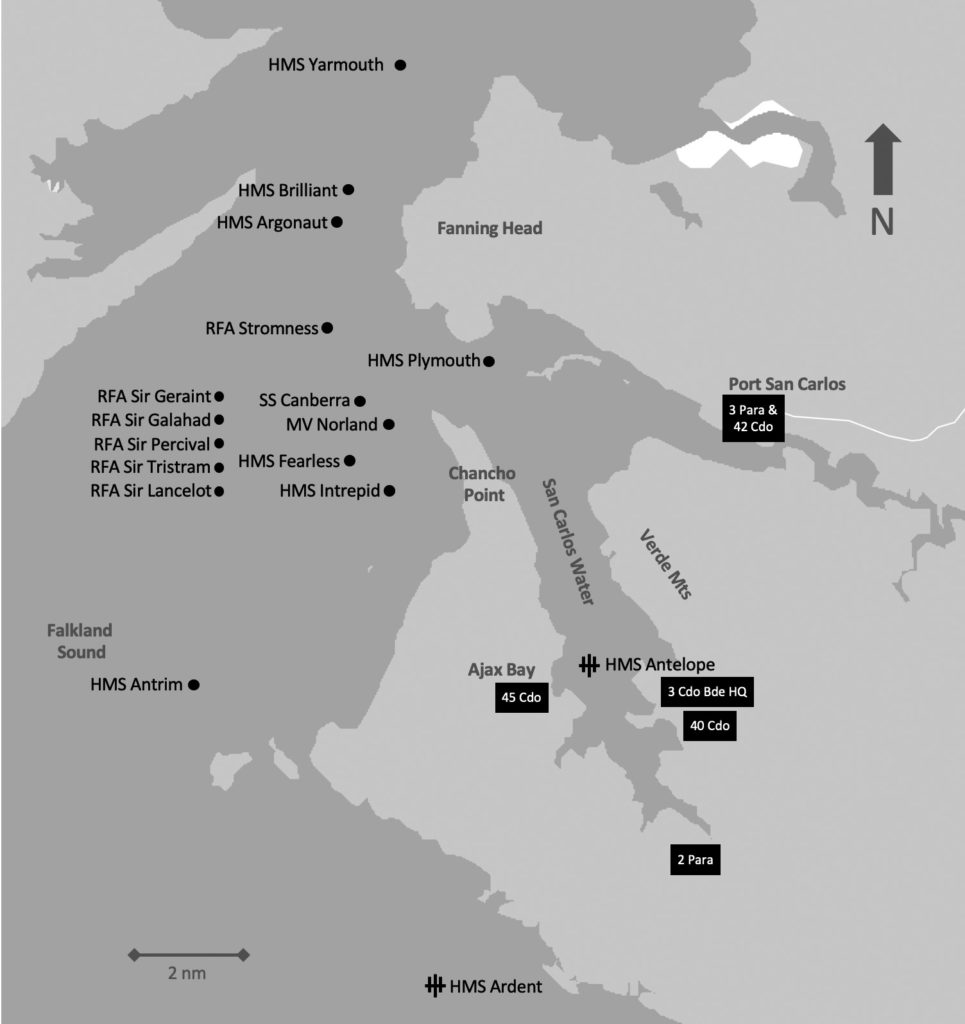

There were two OOWs on the Bridge because we were waiting for our handover. We were doing six-hour watches rotating between ‘bridge front’, ‘up top’ (the Emergency Fire Control Box for the 4.5” Gun on the bridge roof in Arctic conditions) and the ‘back stage’ as we called it (this was running the considerable routines at action stations, checking fixes on the chart, and passing and taking reports from the numerous outstations around the ship). To the reader this may seem excessive, but it was essential to leave the man who was ‘front of house’ as uncluttered as possible from the usual extraneous interferences in a Bridge Watch. We were in a formation of over fifty ships, all totally darkened. If one strained, just visible off the bow was the pinpoint purple blue station light of our neighbour in the screen, RFA Stromness. At 15,000 tons and crammed with ammunition, we needed to hold station and have a healthy respect for affording her sea room.

We must have looked an odd lot had there been even a smidgeon of light. The standard pusser’s issue Action Working Dress had been deemed unsafe for use in action by the powers that be! The reason being that it mostly consisted of cheap 1970s pattern synthetic materials and was, frankly, a fire hazard. We were encouraged to wear instead natural fibres and warm clothing. As you can imagine, this brought out significant latitude in what was deemed to be uniform. In my case I wore my ‘Contract No 5s’ trousers, my Dartmouth rugby jersey, with long johns and a ‘pussers green scrambling net’ vest underneath, topped off by a duffle coat that my Mum had sent (because your grandfather wore one in the trenches and it kept him warm!) – with ‘steaming bats’ and a steel helmet, anti-flash and a life jacket (of note, we had no emergency escape breathing apparatus as it simply wasn’t around in those days). Incidentally, I still have that life jacket to this day.

The wider scheme of things did not mean much to a junior officer, and, at my stage of career (I had been in the Royal Navy about 18 months), I was still pretty wet behind the ears in matters of the navy, never mind naval warfare. However, war, or the prospect of war, has a way of producing enforced maturity like no other human endeavour. The average age of our Ship’s Company was a little over 20 (I was 23), but it was clear to all of us that what we were about to undertake was something momentous. I remember thinking that, however long all of us had been ‘in’, and however many glorious accomplishments the Royal Navy had achieved in its illustrious history, the here and now belonged to us. We were already witnessing events that none of our seniors had seen before in their service, including our Captain, the Heads of Department and the old salts from the Chief Petty Officers’ Mess.

It had already been a long day. The Anti-Air Warfare Co-ord Net (AAWC – “Aawk”), which was on loudspeaker on the bridge, was quiet now, with only the Air Threat Warning update every 15 minutes, being transmitted from a spooky ethereal voice coming from, possibly, HMS Hermes on the other side of the screen or, who knows. The main thing was that it was now ‘Yellow’, having been ‘Red’ for most of the daylight hours.

Our PWO of the Watch, Lt Richard (Dick) Govan, had kept us informed and what he had to say was not great listening. While I realise that, since the campaign, the actual attacks on the force have been analysed in detail, one has to realise that the fog of war is a powerful feature of any conflict and therefore, the picture we had, at private ship level, was almost certainly incomplete. As far as we knew, the Task Force generally had come under sustained attack since the landings at San Carlos had started the previous day. Offshore, where we were, there had been numerous calls of Exocet attacks, long range bombers (Argentinian Canberras) and numerous probes by everything from Hercules C130s to Lear Jets. As to how many of these might have actually happened I leave to history, but the concentrated effect of the warnings, feints, mis-idents and general confusion was telling.

We had spent most of our war thus far in the long range escort role and had only within the past 12 hours or so come into the war zone proper. To my eye the, seemingly, random firing of chaff rockets and illuminants, the violent manoeuvres required in a concentration of shipping and the adrenalin rush that accompanied them was both exhilarating and terrifying at the same time. And on top of it all was the constant threat from Argentine submarines which, we subsequently discovered, did not put to sea other than in South Georgia.

Given the earlier silence, in relative terms, the watch hand over caused its own little commotion. Although whispered, each key player had his turn and we had developed a routine: Tactical Radio Operator and lookout, Bosun’s Mate, then Quartermaster, then OOW2, then the Second Action OOW and, finally, OOW1 or ‘Front of House’. In this particular routine, I handed over to Lt John Frankland, who had just left our for’d two berth cabin, port side, to ascend to the bridge. There was no time for pleasantries but, as I understood it, Middle-watch scran consisted of corned beef hash and beans. I then briefed on the threat, who was on the GDP (Gun Direction Platform) and the state of the 4.5-inch gun. As it was a night watch he could probably look forward to a quiet one aloft but there was a considerable amount of preparation to do for full Action Stations – to be piped shortly before first light (about 0430 Task Group Time, as we were working GMT as opposed to local time zone).

As I was conducting the handover I could hear the Navigator, David Muggeridge, starting his routine. The story that unfolded was one that I recall, even now, with a cold shiver down my spine. For most of our watch we had been struggling to marshal our two latest charges, RFA Stromness and another merchant STUFT (Ship Taken Up From Trade) vessel, called MV Elk – of whom we knew little – into a position on the edge of the screen where we could detach. Both vessels were carrying the bulk ammunition for the landing force and were packed with artillery shells, mortar rounds, grenades, anti-tank weapons and just about anything you could think of that would make a loud bang if damaged. The original plan (by that I mean the one that had been promulgated about 12 hours earlier) had been for us to escort the two ships into the San Carlos landing area under cover of darkness and for Antelope to return to the screen – escort duties again.

However, in the true sense of “no plan survives contact with the enemy” battle dynamics had played a hand. MV Elk had had to cross deck stores to another unit in the force by helicopter and had been delayed leaving her sector. Her maximum speed of around 15kts in lumpy weather meant that it was taking her an age to transit to the outer screen. Thus, we would now be making the transit, at least in part, in daylight. The other major event had been the bombing and sinking of HMS Ardent, our sister ship, earlier in the day and the need for ourselves to undertake her replacement. So, with a little over 12 hours in the Combat Zone, we would be in the thick of it.

But that was for the Morning watch, which was all of three hours away and, given the all pervading need for sleep (I don’t think I’ve ever felt as tired, even in future campaigns and in Command in the Gulf, as I did during my time in the South Atlantic), we would face it when we had to. The Watch left the Bridge in a small huddle and went below, via the Ops Room, where Dick Govan was briefing Lt Henry Watson, PWO(A) and Lt Cdr Robert Guy, First Lieutenant, on the emerging situation. Notwithstanding the change of plan, spirits were high and, in that strange way combat affects the senses, we had a sense of excitement and expectation. We were ‘a Twenty-One’ (Type 21), an elite club in our view, a navy within a navy. What’s more, the enemy had had the affront to attack and kill (we knew not how many, but we knew Ardent had had fatalities) some of our fellow ‘club members’ – and we weren’t going to have that!

So, having left the Command Team, at around 0100 on 23 May 1982, I found myself, having troughed down my beans and stew in the Junior Rates Dining Hall aft, passing the Wardroom. I reflected, perhaps more sombrely on what I had experienced. It had been a long day, our sister ship HMS Ardent had been sunk while defending our forces landing at San Carlos and we were going in to take her place. I dropped in for a welcome cup of coffee. A small pale face poked out of the pantry hatch, it was Mark Stephens, 18, our Wardroom Steward. He had heard, as we all had, about Ardent and asked, in his usual quiet tone “will we be alright Sir?” “Of course,” I replied, in the spirit of ‘up for it’ and ‘can do’ that was still ringing in my head following the brief exchange in the Ops Room. This was to be, for me, the most poignant moment of the whole war, and still haunts today. For by the end of that day, young Mark would be dead, killed instantly in a bombing raid on our ship by Argentinian Skyhawk aircraft later, in the afternoon. He was one, regrettably one of many. But I hope his family will take some consolation in knowing that, to me, he is the one, and hardly a day goes by that I don’t think of him and that fateful moment nearly 40 years ago.

Sleep was a relative term throughout the Falklands campaign. To begin with, on our way South, we had adopted conventional Defence Watch routines, whereby we did a mix of six hour and four-hour watches over a 24-hour period, but this had had to be reviewed. The intensity of operations and the sheer amount to do, from RAS (replenishment at sea) checks (as we had to be prepared to refuel at one hour’s notice), to damage control routines (particularly key issues and returns) to checking on our people (although many peacetime routines had gone by the board, Divisional work, welfare and morale centred activity were still a high priority) and conducting internal and upper deck rounds to support the First Lieutenant, all made for a very compressed day. As a result we had reverted to, at least in the bridge watchkeepers union, our current arrangement of six hour blocks.

As my block had just ended, I would normally expect a six hour off watch period with, perhaps, the luxury of about three hours sleep. However, as we would be going to Action Stations around 0430, it was necessary to grab what one could. This meant proceeding to the For’d two berth cabin, the outboard bunk now having been vacated by my ‘Oppo’ John, who was now on the Bridge, and hauling into my bunk. First, though, having removed my duffle coat, steel helmet and anti-flash gloves, I decided to have a quick wash, shave and the mandatory change of underwear before going into action. I wasn’t to know at the time, but that underwear change would have to last me, give or take, nearly a month until my return to UK and, for reasons I won’t go into here, that would be my last shave for over 40 years. Steaming boots were left on while lying on one’s bunk, but laces were undone and the anti- flash hood brought down around the neck. Thus, fully booted and spurred, lest we have to scramble to our assigned stations, I, like the rest of the Port Watch fell instantly unconscious with exhaustion to await whatever the 23 May 1982 would bring.

The dull “nuh!,nuh!” of the Action Alarm was something we had gotten used to as a regular occurrence only recently as, in that naval era, use of the alarm for anything other than SOCs (Standard Operator Checks) or a live action event, was taboo. Now though, it brought a stirring in the bones and a quickness of heart that I and others were still getting used to. Just now, a little after 0430, it was signalling the abrupt end of a deep but short sleep. I remember the ship was heaving and rolling heavily in what seemed like a confused sea. Tumbling from the bunk, it took a short while to orientate in the red internal lighting before lacing up the boots, donning the external clobber and proceeding, once again, aloft to the Bridge. This time though, the ship was a hubbub with bodies quietly but purposefully making their way to stations. The usual small pool of salt water was sloshing in the corridor having leached in through the for’d screen door, an habitual vice of a Type 21 in a head sea, and made for a tricky passage, given the rolling, to the Bridge ladder. In the semi gloom, I bumped into (literally) our ‘Doc’, Surgeon Lieutenant John Ramage who, with the LMA, was struggling with what looked like an Entonox bottle and a bag of surgical implements. I remember the bag, which looked like a larger version of our green Anti-Gas Respirator (AGR) bags, was open at the top, revealing a startling and rather grim array of surgical implements. I don’t know why exactly, but this set in my mind the utter seriousness of our situation as he was trying to get the whole issue through the small kidney hatch in the ‘Zulu’ opening to 2 Deck to reinforce the For’d First Aid post in the Petty Officers’ Mess.

Back on the Bridge. Still in darkness, but I recall there was a peculiar half light about, with low scudding cloud and a very confused sea. It was my turn to go ‘front of house’. Bridge Action checks were first up – both Olympus gas turbines ‘coming online’; A and B Gyros tested and correct; torpedo alarm checks complete; “limitations 70 ahead 40 astern Port system in auto” – and now to get our bearings. We were in a broad screen sector ahead of our two heavies as the sole escort. No change there then as far as Antelope was concerned.

But then it hit me, and I sensed everyone else on the Bridge at just before 0500. The master plan had failed and, instead of bringing the two most dangerous ships, possibly in the whole Task Group, crammed as they were with high explosives, into the amphibious operating area (AOA) under cover of darkness, we would now be doing so in broad daylight, as we had a good four hours steaming to do yet before we got there. It was an unspoken fear, among many fears in those early hours, and had to be put firmly to the back of the mind.

As dawn broke and the chill forenoon of the South Atlantic beckoned, we got our first sight of the Falkland Islands. From our height of eye on the Bridge, they appeared to differ little from the Western Isles of Scotland and, given that we had recently completed a JMC in the Hebrides, looked strangely familiar. A quick check to port and starboard revealed Stromness, her grey bulk silhouetted against a rising sun, and MV Elk, her dark hull, white upper works and pale blue funnel clearly visible. Up to now we had largely escorted grey hulls so seeing this merchantman, apparently still in ‘civvies’ was indeed a surprise, however, as we were shortly to discover, this was a ‘mixum gatherum’ fleet, made up of vessels of all hues and descriptions.

Steadily, we emerged into full daylight. We were still around 15 miles north of Falkland Sound but could clearly see the tops of the hills around. Smoke, which to the eye looked like gorse fires one would experience on Dartmoor in summer, streamed across both sides of the Sound. But these were not, of course, the result of some natural phenomenon but, rather, the impact of D-Day and subsequent operations, including extensive softening up of Argentinian positions by air and naval fires. As we took this in “Aawk” crackled to life with an “Air Threat Warning Red” and, almost simultaneously, we cringed as two low flying Sea Harriers screamed overhead on their way South towards San Carlos, our next port of call.

It is said that war is ninety percent boredom and ten percent frenzy, or words to that effect. Our war, thus far had, if anything, been rather dreary but all that was about to change and the next hours were to see us in the thick of the action and, for my part, to experience events that have affected me profoundly since. First off, our two lumbering charges were detached, and I remember thinking that Stromness, in particular, seemed to pick up her skirts and get a ‘wriggleon’ to get into the action.

All our radio circuits now seemed to be in full flow and the plan was rapidly emerging. We were to go close inshore off a promontory called Chancho Point at the entrance to San Carlos Water, where the main landings were taking place, there to act as a radar and antiaircraft picket. We were now closing the landing force rapidly and Canberra, stood out like a great white swan brooding over a gaggle of grey ‘cygnets’ that were the warships and landing craft. Merchantmen in various colours littered the inlet and small craft and helicopters scurried to and fro. But, above all, I recall how ordered it all seemed, with an almost administrative feel – not the war scenes that one had experienced in the movies. But this was the arch deception of RAdm Woodward and, principally, Cdre Mike Clapp, who had master minded the landings to have them take place in a location offset and remote from the enemy’s main centre of gravity. Nonetheless the ruse had now been exposed and, successive air attacks having taken place over the past two days, another visit by Argentinian air to what was now know colloquially as ‘Bomb Alley’ was inevitable. Nonetheless we snuggled up in our sector, did crew rotations (it was my turn on the GDP) and had a kind of breakfast consisting of tea, a meat ‘bap’ of some description and, perhaps oddly, a packet of fizzy sweets called Freshers. We all thought the ‘Can Man’ (NAAFI Manager) must have had some slow selling stock to get rid of!

Action, at least our first taste of it, came in the form of our Lynx helicopter being launched to attack an enemy freighter that had been spotted in the South of Falkland Sound and Lieutenants Tim McMahon (Flight Commander and Pilot) and Gary Hunt (Observer) took off looking particularly war like carrying a couple of Sea Skua missiles. The fact that these were live and about to do real damage steeled all of us in the Bridge/GDP team and gave us a sense of purpose and pride. The boys did the job, but the ‘21s’ were a club and no one got away with doing anything, good or bad, without an element of ribbing or perhaps what would be known as “bants” these days. So, on their return, having attacked and damaged the freighter, McMahon took the Lynx screaming down the starboard side. For reasons I can’t quite recall now, the entire team had made up ice skating type score cards and held them up to greet ‘424’ (the aircraft number) – 5.9, 5.9, 5.6 etc and a big one which read “Argentinian Judge 0.0!” It was, however, on their second sortie of the day, while doing a damage assessment on their target, that McMahon was illuminated by a fire control radar and, as he dropped to 40ft and increased speed, was overflown by a formation of Skyhawk aircraft. I was by now back on the Bridge and recall his voice coming up on a standby radio called ANARC which was crystal clear calling out “overflown by four fighter aircraft carrying centre line and wing stores.”

So this was it. The past six weeks had led to this. We had been at Action Stations since dawn and now adrenalin began to take over. I think it was John Sharp, then on ‘front of house’ who called our first sight of the enemy. Four aircraft shot across the mouth of San Carlos, we thought they were Daggers (Mirage 3 variants) at first, but the tail aircraft clearly had the snub nose and prominent underwing tanks of a Skyhawk. There is something very cold, not fear, but a deep sense of your own mortality that hits you when you confront something or someone who’s only aim is to kill you.

The aircraft went behind a nearby hill and disappeared from view for a while. The next few seconds require a little explanation. When the navy does gunnery practice in peacetime, everything is very orderly and deliberate. Screen doors are shut tight, upper deck out of bounds, weapons on a safe bearing etc. But this was war. Because we had to manoeuvre in a postage stamp of a sector, with over thirty major vessels and myriad landing craft, helicopters, small boats etc in close proximity, we had, of necessity, left both Bridge doors open so that we could quickly move from one wing to the other. We also needed to get ammunition and other supplies to the Gun Direction Platform where we had SLRs and Light Machine Guns mounted.

Thus, after a couple of minutes, we were brought bolt upright by the deep roar of our Starboard 20mm Oerlikon gun and the Bridge filled with the smell of cordite and smoke. The aimer, Leading Seaman ‘Bunny’ Warren had laid his sights on the lead Skyhawk which had come in below Bridge height (actually about 30 feet). Warren later said that he “drew a bead, closed his eyes and just kept firing.” He scored a direct hit but not before the aircraft released two bombs. One went between the mainmast and foremast and burst into the sea on the Port side but there was an ominous thud through the ship as the other hit our Starboard side.

Having dived for cover, I remember coming back up and looking out over the Port Bridge wing to see the aircraft opened up like an Airfix kit and a mass of fragments in the air with a massive orange fireball. I distinctly remember the engine, still more or less intact, heading purposefully out into the water trailing sparks and debris. The pilot was killed instantly but, I have to say, on the Bridge we cheered in a manner befitting a world cup win. Our Captain, thinking that we had indeed been struck and he was hearing the screams of the wounded, came sprinting up from the Ops Room below, by which time every man was back at his post and looking out for the next wave. Meanwhile, the DC comms phone from the GDP whirred, it was John Frankland from ‘up top’ – “all well nobody hurt but we’ve lost the main mast!”. In pulling up the Skyhawk, which had already been hit by several rounds from the Oerlikon, had gone through the main mast – Antelope had used one of her horns!

The noise was incredible as every ship in ‘Bomb Alley’ had opened up – 4.5-inch guns, Bofors 40mm, Oerlikons, GPMGs and, of course Sea Cat and Sea Wolf missiles. We ‘did our bit’. As a second wave of two Skyhawks closed seconds later from the Port side, our 4.5-inch gun, which had been restricted to starboard due to the proximity of land, opened up with several rounds. We also engaged with our one Sea Cat launcher aft loosing off, firing at the second of the Skyhawks. This was fired by Petty Officer Lazarus and visually aimed. It exploded under the aircraft’s wing and, as subsequently reported, caused mission abort damage. So, I credit us with two kills and, of course, the freighter previously engaged by our Lynx. However, although we beat off the second attack, one of the aircraft had released bombs and one of these came through on the Port side. Again, the ominous thud. I have a picture on my wall to this day of the ship post attack and the hole in our Port side is still clearly visible, about 20 feet below where we were all standing. If it had exploded….

Chaos reigned, at least in the immediate aftermath of the attack. The whole ship seemed to wreak of an oily smoke. Numerous alarms were going on the Bridge front panels: Gyro, Steering Gear, Torpedo alarm, you name it. A “Whrrrr” on the DC Comms phone. “SCC permission to shut down Starboard Olympus – we have engine room damage Sir”. The Olympus had developed an unearthly roar and was belching white smoke everywhere, probably because the bomb had opened a large hole in the exhaust and was now nestling between the Aft engine room and the Auxiliary Machinery Room – though that was not apparent at the time. Our gyros had both been blown out and the repeaters had gone into a spin. Training clutched in. I distinctly remember writing “Cadbury’s Dairy Milk Very Tasty” (Compass, Deviation, Magnetic Variation, True) in chinagraph pen on the captain’s console. As if by instinct, we fell into a pattern; John Sharpe on the con Port side, ‘Navs’ at the Pelorus and chart and yours truly reading out the converted magnetic headings off the magnetic compass repeater above the captain’s chair.

It dawned rather slowly on us all that, put simply, we were alive. Surely bombs hitting the ship should do more damage than this? (Remember no one had experienced this for 40 years). Just then Lt Cdr Robert ‘Bertie’ Guy arrived on the Bridge. Guy, ex Royal Yacht and a former Equerry to the Prince of Wales, he was a sight for sore eyes. Dressed in pressed doeskin trousers tucked into mess boots, woolly pully with a crisp white shirt, black silk cravat and his trademark beret, he looked like a cross between Tony Hancock and Pablo Picasso! He immediately went over to the Bosun’s Mate’s console and said “Officer of the Watch I’d like to make a pipe to the Ship’s Company.” What he said was sobering. We had taken two bombs, one for’d, one aft, neither of which had gone off and Steward Stephens (whom I mentioned earlier) had been killed. Though this was a shock, there was no time to hoist it all in. The Captain, Nick Tobin, had arrived on the Bridge with the Yeoman. We were using the Clansman radio and Bridge tactical radio set as our main comms were down. “Yeoman – make to COMAW: not very well, request anchorage to conduct damage repairs and unexploded ordnance disposal.” In this regard, we were not alone. Several ships had been damaged and, for reasons unclear at the time, a number of the bombs dropped by the Argentinians had not gone off, despite their pilots showing enormous bravery (and recklessness in some cases) in pressing home their attacks. We were assigned an anchorage in Ajax Bay, further down San Carlos and had the novel experience of piloting the ship with no gyro and no radar. I remember we used every primitive aid; Stuart’s Distance Metre, Weymouth Ross Range Finder, sextant angles etc. and took relative bearings for fixes as we weaved our way past the full landing force, holed in both sides, billowing smoke and with our main mast bent to look like a malevolent Archbishop’s crozier, what a sight.

We anchored … and then waited. Waiting is the worst and most enduring part of war and being sat with two 1000-pound bombs waiting to explode was not a pleasant experience. It was late afternoon and the gloom had started to descend when two SNCOs, WO Phillips and Staff Sergeant Jim Prescott of the Royal Engineers were inbound to us from another ship. I saw both men briefly as they arrived, escorted by our MEO, Lt Cdr Richard Goodfellow. I had been on a Damage Control patrol around the ship with a small party of ratings. We had passed the bomb entry point For’ard, where young Mark Stephens had been killed and seen the destruction the bomb had caused there. It had come through the Ship’s telephone exchange and Petty Officers’ Mess and the nose seemed to be ‘tucked in’ in a bunk space. We never saw the Aft bomb.

A decision had been made to evacuate the bulk of the Ship’s Company to the upper deck and divide into two large parties, one on the foc’sle and the other on the flight deck. I went to the Flight Deck, along with Lt Dick Govan. There we waited in the descending darkness while to bomb disposal team did their work. The cold began to bite and, although nobody showed any open signs of it, the underlying tension, knowing that just below us was an unexploded ‘thousand pounder’ was palpable. We rotated crews, including me, through Fearnought and breathing apparatus so that at any stage we would have a ready ‘Attack Party’ to deal with the damage. We had a range of portable fire extinguishers and the Rover gas turbine pump available, but the fire main and electrical power aft had been damaged by the bomb on entry. News had come back that three attempts had already been made to defuse the bomb without success and that the team now were going to attempt a fourth using a different method.

At that attempt, the bomb exploded. There may be others reading this that have had the unwelcome experience of being within a few feet of a large bomb when it explodes but, for the majority who have, mercifully, not been exposed to it, I can only say that everything goes into slow motion. The bang must have been tremendous but, strangely I have no recollection of that. Instead, I recall the sight, apparently in slow motion, of most of us assembled on the flight deck being thrown aft and, at one stage, being in mid-air. The sky above was littered with radiant white sparks. Shock was suppressed by adrenalin and the immediate effect was for people to go off in all directions. I saw Richard Goodfellow, his head poking out of the quarterdeck hatch shouting for first aiders. WO Phillips had lost an arm and Staff Sergeant Prescott was killed instantly and he and CMEM Porter were badly shaken. Meanwhile Dick Govan and several others were attempting to get the Rover going. As I was in Fearnought, along with ‘Bunny’ Warren and two others, we lead out a hose from the Rover up to the boat deck to attempt to fight the fire. The bomb had torn a 35ft wide hole in the ship’s side from the boat deck to the waterline and both engine rooms were on fire. Ammunition was cooking off in the 20mm magazines and a thick acrid smoke was broadly dividing the ship in half. When we eventually got the hose in place, the pressure was pathetic, however a small landing craft, which was far too close for safety, was already pumping water into the hole from his onboard pump. Type 21s had aluminium superstructure and I remember seeing it literally melting before my eyes. A thump on the shoulder from ‘Bunny’ – “No. f***ing use Sir – the Sea Cat mags about to go”. We were indeed in close proximity to our Sea Cat ready use magazine and, given that we had no water pressure, had to withdraw.

The Ship’s Company fought the fire for about an hour, and subsequent records show that, in 43 minutes, the ship had burned to the water line. A cross wind of about 20kts meant that we were effectively blinded. Dick Govan was adamant that we were not abandoning when I got back to the flight deck but, in the end, it was hopeless. Robert Guy arrived by the hangar and said that the Captain had given the order to abandon ship. But, with zero visibility and choking smoke, finding one’s way off was no easy matter. A – no doubt well meaning – helicopter had taken station in a low hover off the Port quarter and this was whipping smoke across the flight deck. Through this, though, I could clearly make out a rather incongruous looking queue of men looking as though the turnstiles had just opened at Twickenham. They were boarding a landing craft close aboard on the Starboard side so I made for that. I must mention here, the outstanding bravery of the Royal Marines Landing Craft crews and Corporal Alan White of LCVP Foxtrot 7 (HMS Fearless) in particular, without whom I would most certainly not be here today. He later received a CINCFLEET Commendation from Admiral Sir John Fieldhouse for his action that night. Getting to the quarterdeck, which had a low freeboard in a Type21, I realised that water was lapping over it. I also needed to rapidly discard my Fearnought suit as, if I missed my step, thick wool saturated would undoubtedly take me to the bottom. I got the bottoms off and my lifejacket on and was conscious of Dick Govan bellowing at me to get in the boat. A slip, a step, a dunking, some floundering and spluttering and I washed up on the half-lowered ramp of the LCVP like a landed fish. I was immediately bear hugged by my cabin mate, John Frankland, who had thought the worst as he was in the For’d party when we lost comms. Forty one of us were lifted clear by the LCVP and, within five minutes the aft Sea Cat magazine exploded, giving the world the iconic photograph that heads this article. Dick Govan turned to me and said that it was his little girl’s birthday that day and this was a fitting fireworks display.

We were taken, initially, to HMS Intrepid, the other LPD in the bay. In transit I felt my face getting really cold and wet which, at the time, I put down to the dunking. However, on arrival in Intrepid, judging by looks I was getting, it was apparently something more. In common with many, I had suffered light flash burns across my face and looked like something from a zombie movie. I have never smoked, but on arrival on Intrepid’s tank deck, someone thrust a lit fag into my hand and, without even thinking, I took a drag. I was reported as being “steady under fire” in my S206 (predecessor of OJAR) from Antelope, but I remember seeing my hands shaking uncontrollably as I pulled on the cigarette. The body does strange things under shock. Eventually, after ‘pot mess’, tea and a gallon of water (we were very dehydrated), I was shown a bunk in Intrepid’s embarked force accommodation. Before I collapsed I looked at my Seiko illuminated watch – 0110 on 24 May, almost exactly 24 hours from leaving the Bridge after the ‘long First’ – the longest day of my life.

Now, 40 years later, there is still hardly a day goes by that I don’t in some way reference the memory of HMS Antelope. She was a fine ship, with a fine Ship’s Company, but, I think, the finest testament to her comes from our Captain, Cdr Nick Tobin DSC RN who said in Our Falklands War (Geoffrey Underwood, Maritime Books 1983): “I think I was the last to leave her. I climbed down a knotted rope into a Landing Craft. I felt a sense of shock, probably frustration more than anything else. I felt cheated. It all happened so quickly. The boys were all very calm indeed… In action they were superbly professional and steady. I never saw one man flinch or turn away or not do his duty to the best of his ability. I think the average age of my Ship’s Company was just 21… Looking back, I feel a sense of pride in my Ship’s Company for what they did all the way down to the Falklands and what they were in action and subsequently. The psychological impact of losing the ship, losing friends and seeing friends injured is very great. I was proud of the way they handled the whole thing. Some people think the youth of today are not as good as the youth of their day. My Ship’s Company was the finest bunch of young lads I have ever served with… There is nothing special about them. They are young men who happen to have chosen the Royal Navy as a career. They are a product of the English character; a certain amount of pragmatism; good training and pride. It all combines to make some very good people…I think we did our job well. There was only a millimetre in it either way when the bomb was being defused. If it had been defused, we would have survived to fight throughout the operation. It was frustrating not to be able to complete the job we had started so well.”

Cdre Russell Best OBE RN (Rtd)

& Staff Sergeant Jim Prescott RE (Age 37)