Some Principles of Maritime Strategy Making IN THE ROYAL NAVY TODAY

Captain Dr Kevin Rowlands RN

By the Editor – The author demonstrates the centrality of history and geography to the study of strategy. Historical example and appreciation for geostrategy provided Sir Julian Corbett with the foundations for his principles of maritime warfare, making his contribution to grand strategic thought both relevant today and indeed timeless. A 5 minute read.

What is strategy? Despite having worked in various jobs with ‘strategy’ in the title, and having been responsible for delivering policy and strategy education to our brightest and best officers at the Staff College, I’m not always sure what it is. If someone put a gun to my head and demanded a quick answer I would probably blurt out a standard response about ends, ways and means. I think the means are our ships, submarines, aircraft, and people. I suppose the ways might be those particular attributes of navies we always talk about – persistence, poise, lift, leverage and so on. Or maybe they could be Ken Booth’s trinity of military, diplomatic and policing / constabulary roles.[1] Today we might call that trinity warfighting, international engagement, and maritime security. But Ends? What are they?

And that is perhaps what is wrong with the ends, ways and means description of strategy. It requires ends, but the business we are in is continuous. It doesn’t have neat end states. There is no ‘mission accomplished’ moment and, if there is, we should view it with deep suspicion.

Would Sir Julian Corbett recognise any of this? The 21st Century world of undersea cables and Artificial Intelligence aside, I think that he probably would. As an historian of maritime strategy I think he would be comfortable with today’s issues if he were given an hour or two to orientate himself after waking up from a century of cryogenic stasis. Actually, as an early 20th Century liberal imperialist (and here I make no political comment or endorsement!) I think he would probably be more familiar with a post-Brexit Global Britain than he would have been with a Cold War bipolar world with the West following a strategy of containment.

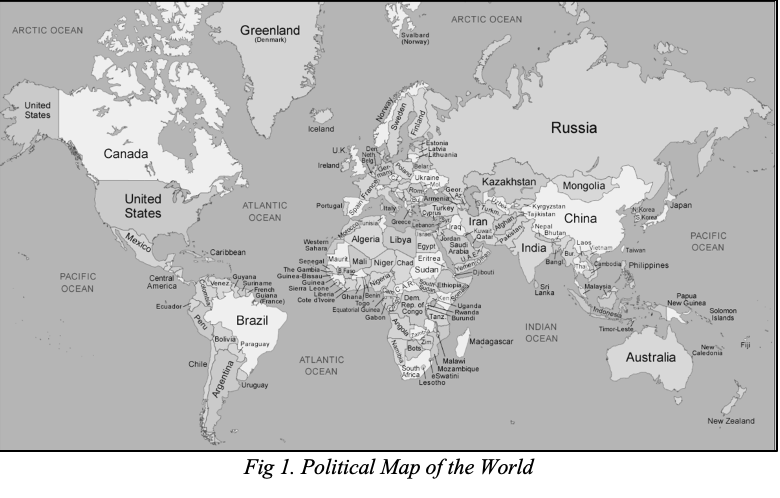

So what is the UK’s maritime strategy today, and how is it made? In grand strategic terms, we can probably work it out ourselves given a simple map of the world.

We can stare at that map and overlay our own thoughts on what needs to be done and where to further the UK’s interests. We need to defend our island nation. We need to deter Russia and China. We may need to defeat one or both of them in war. We certainly must compete with at least one of them economically. We need to do this in concert with our partners, both in Europe and the wider world. We need to stand by our Allies. We need to protect our overseas territories. We need to protect and enhance trade, especially in the economic powerhouses of the Indo-Pacific. We need to be mindful of emerging crises and how they might affect us. We need to reassure our friends. In short, as a global maritime nation we need to be everywhere and that is where the Royal Navy comes in. That is difficult, however, because being globally engaged is a stretch for any navy and is certainly a stretch for a medium power such as contemporary Britain. It means making difficult choices, balancing priorities, and sometimes robbing Peter to pay Paul. That is why we need a good maritime strategy to deliver it.

Do we have such a strategy? Yes, we do, and Corbett would have understood that it is driven by history, geography, economics, technology and perhaps most important of all, relationships.

“Operating at the heart of the Integrated Force, the Royal Navy will protect the United Kingdom’s security and prosperity by promoting our influence and interests through persistent global engagement, contributing to the free and lawful use of the seas and, as a leading contributor to NATO Deterrence and Defence, standing ready to war fight alongside our allies at and from the sea.”[2]

This articulation of strategic vision tries to go beyond mere programmatics and the description of the Navy’s equipment programme that has sometimes masqueraded as strategy in the past. This, at least, is grounded in grand strategy, foreign policy, and the reality that other services and other domains or environments, and allies of course, have got to be considered. As Andrew Lambert has pointed out in 21st Century Corbett, his slim volume on the great man, Corbett understood the primacy of national or grand strategy, and that single Services could not write their own in isolation.[3]

A knowledge of history is essential in strategy-making but in this context we must mean applied history. We should not be ignorant of the past, nor be slaves to it, but we should identify and learn the lessons of history, whenever and wherever appropriate. Many of us may find the Seven Years War interesting but professionally, unless we are studying it to pick out its’ relevance and applicability to today, it is nothing more than a good yarn. Corbett knew this when he wrote his histories and made them applicable to his times. We must do the same today.

History is important to the UK and to the RN. In particular, our historic ties to much of the world are incredibly relevant. The fact that the Royal Navy remains the reference navy for so many other navies is also incredibly important. It carries responsibility but it carries opportunity too. We want to stay a, or the, reference navy particularly for four of the Five Eyes community navies and the Commonwealth, and our strategic approach factors that in. It speaks to friendship, cooperation, commonality, interoperability and interchangeability.

One of the principles of maritime strategy making in the Royal Navy today, therefore, is to acknowledge our history and apply its lessons to today’s world. Each of the Services has an historical branch. In the RN the Naval Historical Branch sits within the Strategy and Policy division. Its counsel is sought. All Naval officers to a greater or lesser extent are taught history. All of our strategy-makers, staff trained as they are, have been educated in the importance of history.

Geography is important. Human geography. Physical geography. Political geography. Alongside history, we need to acknowledge the major role geography plays in strategy-making. Russia’s maritime strategy and the composition of its four main fleets are a factor of its immense geography. Switzerland has no navy because of its geography. England, then Britain, then the United Kingdom, again as Andrew Lambert pointed out in his book of the same name, was and is culturally a ‘seapower state’ because of geography.[4]

The Mackinder Forum, a geopolitical forum mainly online which was established in this country by Geoff Sloan and the late Colin Gray, states as its mission that “the conduct of foreign policy requires that a state’s objectives and demands be projected through space to specific geographical locations.”[5] Navies, including the Royal Navy, are superbly placed for obvious reasons to project that foreign policy.

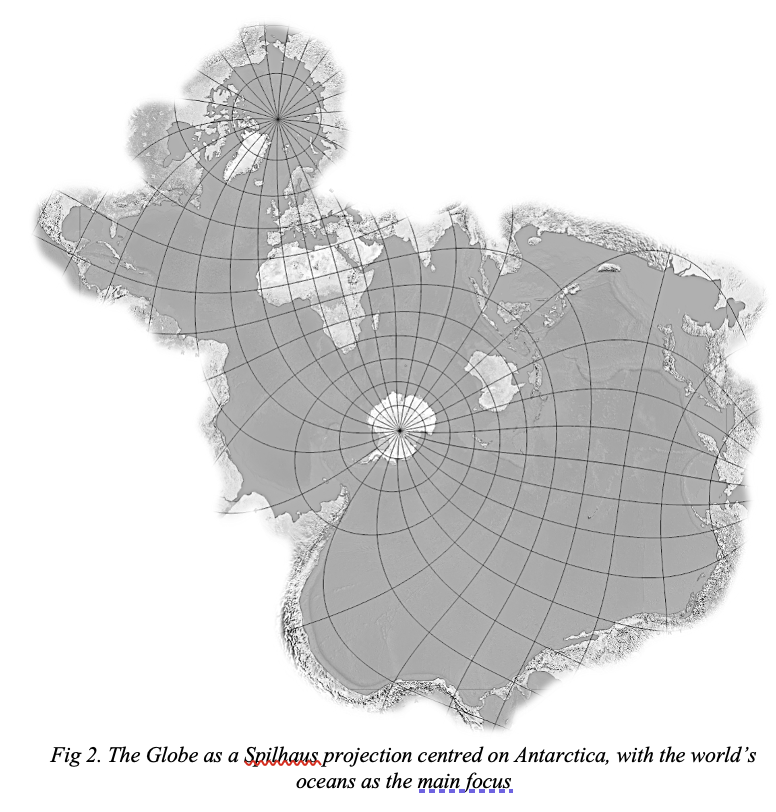

There are of course different ways of looking at geography. The map (Figure 2), the Spilhaus projection, is more than a trick of cartography. It indicates a mentality. There are those who famously speak of world islands, but there is also a world ocean. There are those continental powers who famously approached the sea and as obstacle rather than a manoeuvre space. The UK and the Royal Navy have never fallen into that trap. Our strategic outlook has long been an outward one of exploration affecting events on land from the sea and at sea.

But geography is not a static discipline and the world changes. We need to consider these changes when making strategy, factoring in the implications of climate change, of demographic shifts, and of global migration. Our strategy must recognise that there will be parts of the world opening up to us now and in future which were previously inaccessible. And conversely there may be regions currently familiar but where we may struggle to operate in the decades ahead. We all know about choke points but in the usual projections we use such as Mercator, one tends to disappear off the top of the map. How important will the Bering Strait be in 2050 when the Northern Sea Route and Northwest Passage are the standard routes of choice? Who will, who can, close that strait or force it open? How will missions change as the world changes?

Is listening to geographers such as Sir Halford Mackinder the same as turning our backs on Sir Julian Corbett? Of course not. They knew each other. They were from the same world. Liberal Imperialists, they were both members of the Coefficients Dining Club.[6] They both dabbled in politics. They both applied their discipline to the issues of the day, many of which are the issues of our day as well. The world of Mackinder and Corbett a century ago was a world of England and Empire before and during the First World War. A time of skirmishes and peace and limited war and war of national survival. What parallels might our strategists draw to today?

Economics is deemed the dismal science. Dismal it may be but it is important. Of course our strategy should be based on the threats we face and the relationships we wish to build with friends and Allies, but strategists must also make their vision and plan affordable. Analysis of defence spending can be both surprising and fascinating. Modest increases in budget, i.e. a percentage point or two of GDP, don’t lead to any significant leap in capability or operational effectiveness. The big jumps are when the economy is on a war footing.[7] So what? The principle for today’s maritime strategist is that they need to live within their means. Unless major war comes knocking, the big picture probably isn’t going to change much.

We are all aware of rising inflation but what is less well known is that, globally, defence spending has been consistently rising. However, the buying power is those dollars, pounds, euros, rubles, and yuan is reducing. The gap between nominal and real growth is widening. The impact will fall on personnel, on operations, maintenance, procurement, and research and development. So a maritime strategist today may well have to think about how to project that foreign policy, or maintain that persistent global engagement, with fewer people, or fewer ships, or ships that require less maintenance and can deliver greater availability. We use horrible words like productivity. Would Corbett recognise this? Yes – the Coefficients, the dining club he attended with Mackinder and others, were champions of efficiency.

These considerations might bring into focus ideas of concentration or aggregation of forces versus distribution and dispersal. They might make us question the most operationally effective and cost effective force mix. But some of those things rely on technology, so it is worth considering how that affects strategy-making.

Does strategy drive technology or does technology drive strategy? This is an interesting question deserving of more attention itself. In the time of Corbett, Admiral Sir Jacky Fisher mused that strategy should determine what ships we have, that the ships we have should determine the tactics we employ, and that those tactics in turn should determine the armaments we buy.[8] For armaments let’s assume we mean weapons, sensors, and so on. It seems a logical progression of thought, but is it true today? Was it true even then? When we procure ships, as we have with the Queen Elizabeth-class carriers, and declare that they will be in service for over 50 years then we are accepting that the life cycle of our policies (and therefore our strategy) will almost certainly be less than the life cycle of our platforms. A half century period, give or take, would have covered withdrawal from east of Suez, Cold War containment, war in the South Atlantic, liberal and humanitarian interventionism, and taken us into wars in the Middle East. Few if any were predicted ahead of time.

Another principle for maritime strategy-making therefore is to fight for the capabilities we think we need in the future, and to use now those capabilities that our predecessors thought were the right choices when they were making decisions. It is about using ships designed to hunt Soviet submarines in the cold of the North Atlantic to escort merchant vessels through the heat of the Bab-el-Mandeb and Strait of Hormuz. It could also be about using drones and artificial intelligence, keeping sensor and shooter on task near permanently. Those considerations for the strategy-maker may be that new technology is not only more cost effective, it is more militarily effective and reduces risk to life. Or perhaps it raises risk to life as the tactical decision maker never needs to think about having to write to a bereaved family when it all goes wrong. Perhaps the tactical decision maker isn’t even human. Another consideration for the maritime strategy maker is the ethics of any given situation.

To conclude, what are some principles for maritime strategy-making today? I would venture that maritime strategy is for both peace and war, and that it can never be made in isolation. It needs to sit below grand strategy and foreign policy and alongside other environmental strategies. It needs to consider the realities of history, geography and economics. And it needs to be aware of emerging technologies and how they will shape the world. It also needs to be cognisant of the ethical implications of all that we do. I think that Corbett would understand.

References

[1] Ken Booth, Navies and Foreign Policy (London: Croom Helm, 1977), pp 15-16.

[2] Royal Navy Strategy, 2022.

[3] Andrew Lambert, 21st Century Corbett (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2017), p 3.

[4] Andrew Lambert, Seapower States (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2018).

[5] Mackinder Forum, “Mission”, https://mackinderforum.org/ (accessed 20 May 2022).

[6] Andrew Lambert, The British Way of War (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2021), p 84.

[7] Conclusion of unpublished analysis by the Naval Historical Branch, 2022.

[8] John Arbuthnot Fisher and Peter Kemp, The Papers of Admiral Sir John Fisher, Vol. 2 (London: Navy Records Society, 1964), p 6.