The Merchant Navy Is Our Jugular Vein

In a June 1946 article for the Commonwealth and Empire Review, Admiral Sir Frederic Dreyer detailed the vital importance of anti-submarine warfare for the protection of Britain’s merchant shipping. An expanded version of the article was published in the NR [34/3, p. 243], with Admiral Dreyer taking to task the ‘bomber mafia’ who had favoured the strategic destruction of Germany over the imperative to protect Britain’s convoy lifelines. Admiral Dreyer’s article is republished here as part of the 80th anniversary of the Battle of the Atlantic. A 20 minute read.

The Royal Navy and the Merchant Navy have never served the Sovereign and the Realm better than they did in the two World Wars. In 1939 Germany sent her submarines out on to the trade routes before the declaration of war, and a W/T cypher signal on the 3rd of September 1939 started their submarine war in full blast against our shipping. We had to wait until then before commencing to arm defensively thousands of merchant ships.

The ships (including aircraft carriers) of the Royal Navy sailed with our merchant ships and fiercely attacked, in all weathers, the enemy vessels and aircraft encountered in the Seven Seas and were finely supported, where possible, by coastal aircraft of the RAF. Nevertheless, the officers and men of the Merchant Navy had to show unbreakable fortitude throughout the war in the face of terribly heavy losses, in order to enable us and our Allies to survive. They deserve one of the large shares of the credit for the final triumph.

Convoys and Escorts

Jellicoe instituted convoys in 1917 to counter deadly submarine attacks on shipping. In 1917, realizing the huge target a convoy presents, he refused to put the Merchant Navy into convoy until he had increased escorts available. In 1934, then aged 75, he wrote a book, The Submarine Peril, [see NR 22/4, p. 760] in which he warned that “fast vessels needed for escort against submarine attack cannot be improvised.” This warning was not well heeded; and we paid for that in ships, cargoes and sailors’ lives.

The Duke of Marlborough, during the War of the Spanish Succession, wrote to one who pressed him to interfere in the actual conduct of naval operations: “The Sea Service is not so easily managed as that on land. There are many more precautions to take and you and I are not capable of judging them.” So special weight must be given to the opinions of sailors on operations at sea. The German Navy, fortunately, did not realize until late in 1940 that their submarines should make ferocious massed and sustained night attacks on our convoys.

In the Second World War the Navy, Army and RAF cooperated magnificently. It is of vital importance to maintain this unity.

I had the good fortune, although retired in May 1939, to be employed in the following posts until I became over 65: (a) Commodore of Atlantic Merchant Convoys, October 1939 to May 1940; (b) when France fell I was appointed Admiral on the Staff of the GOC-in-C, Home Forces, for Anti-Invasion duty for five months; (c) then, in the autumn of 1940, I was appointed Chairman of an Admiralty Committee to assess the number of enemy submarines destroyed. We took much evidence, which put me fully up to date in anti-submarine warfare. Our assessment of enemy submarine losses was correct; (d) Inspector of Merchant Navy Gunnery (February 1941 to July 1942). The duties included teaching the Merchant Navy how to shoot down low-flying aircraft; (e) Chief of Naval Air Services (temporary) (July 1942 to January 1943).

The Security of our Sea Communications

Aircraft carriers were developed by the British and American Navies and persisted with, in the face of opposition from people without sea sense. They proved of decisive value in the Pacific and Arctic Oceans and in the Mediterranean, and also of very great value in the Atlantic.

Many people now realize that our terrible losses in merchantmen in 1942 were largely due to the subordination of the needs of sea warfare to the policy of bombing Germany. There were not enough aircraft of suitable types fully to perform both duties in 1942 and 1943. A well-known RAF officer told us in a broadcast in the winter of 1944 that it was in the early months of that year that Bomber Command had proved that they had developed a new capacity to hit precise targets, such as oil plants, at night. The chances were not great in 1943 of seriously damaging enemy submarines by bombing them whilst building.

Having safeguarded the British Isles against capture by stationing powerful naval forces in home waters, and with the growing strength of the RAF, who had won the Battle of Britain, the security of our sea communications was our primary requirement, for we cannot live without them. Instead, the war industries of the enemy were made the first objective. Not only did the bombers engaged on this duty fail, notwithstanding their great valour, to destroy the war industries in 1942, but our supplies were exposed to destruction in 1942 through giving them insufficient protection at sea.

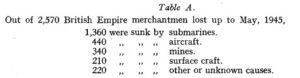

Losses of Empire Merchantmen v. U-boats

Evidence of the error committed is shown by our losses, recently made public, and in the returns of the sinkings of enemy submarines.

Protection of shipping lies in destroying the attacking craft or projectiles, whether piloted or not, and in sweeping up mines.

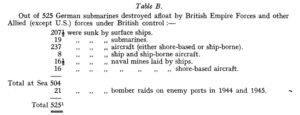

Tables A and B give proof of a fault in the direction of our air effort [see also NR 34/2 p. 126]; for, while submarines were the most destructive of all the instruments used by the enemy against our shipping, aircraft were one of the most effective of the instruments which destroyed the enemy submarines; and aircraft, covering our shipping, should, therefore, have been heavily reinforced long before this was done in 1943.

Various writers in 1942 produced an unfortunate effect by claiming that the most effective mode of beating the enemy submarines was to destroy them by air attack while under manufacture. They believed in winning the war by bombing. Bombing is, of course, very unpleasant, as shown at Hamburg in 1942; but, even with the accuracy achieved in 1944, bombing alone did not induce the Germans to sue for peace. They were conquered and occupied by Allied armies supported by aircraft.

Bombing failed to prevent the Germans turning out large numbers of submarines. For example, at Bremen in 1945 we found sixteen large submarines ready for launching. Bombing shipyards and factories did make submarine construction more complicated, but that in itself was not a full return for the hideous loss of our shipping and vital food and war cargoes (including hundreds of thousands of tons of petrol for the RAF and for the Army, Navy and other Services), due to the inadequate allocation of bomber cover – although the fitting of additional tanks to airplanes to increase their radius of action had been put into practice early in 1942.

Have in mind that it was at sea we destroyed 504 German submarines (see Table B). It was not until 1943 that really adequate numbers of bombers were transferred to provide cover for our shipping. This could have been done early in 1942, leaving bomber force available to damage German war industries and create havoc in communications and carry out sea mining on nights unsuitable for bombing.

The bombing of Germany also did fine service in drawing large German air forces away from the Russian front. Our brave bomber crews did very important work.

Borrowed Spitfires Converted for Deck Landing

In 1942 the Navy found it hard to get the numbers of most modern types of aircraft required for the Fleet Air Arm because the bombing of Germany took precedence and absorbed a very large percentage of our aircraft production capacity. They borrowed some Spitfires and converted them for deck landing for our carriers for the North African landing, made in November 1942; but they could not then get the aircraft production capacity to manufacture enough most modern aircraft fully to equip the fleet carriers, escort carriers and merchant carriers under construction. The Fleet Air Arm required to be trebled in order fully to man and equip the above carriers, etc.

All naval officers were naturally greatly concerned at the very grievous losses being suffered in 1942 by the Merchant Navy other than our troop convoys, which, being much faster and more heavily escorted, were almost immune from submarine attack.

Over 6.25 million gross tons of Allied merchant shipping was sunk by enemy submarines in 1942; i.e., more than double the figure for any other year.

I was not involved in the Admiralty operational control of Coastal Command (RAF), but by November 1942, although my hands were full of my own work, I had formed the opinion that far greater long-range bomber cover should be given to the Merchant Navy, because to reduce the heavy toll being taken of them by submarines was even more important to us than the bombing of Germany.

In the first week in January 1943, I suggested that some hundreds of long-range bombers should be lent to strengthen the air cover of the Merchant Navy. Also that more shore stations should be established from which long-range bombers could operate to cover our convoys.

I told the Minister in another Department of State that in my opinion the terrible losses in our Merchant Navy were largely due to too much weight being given to the bombing of Germany and that as a result insufficient long-range bombers and escort-carrier aircraft were available for protecting our merchant shipping. I realized that such matters would no doubt be decided at War Cabinet level.

“400 Masters of Merchant Ships Missing”

Shortly after this I heard that over 400 of the masters of merchant ships were missing; and, when I told a commodore of convoys that I had lost one merchant ship torpedoed and sunk in the Atlantic in the winter of 1939, he said that in one convoy in 1942 he had thirteen ships torpedoed and sunk in the Atlantic in four days.

It was easy for me to realize what a tremendous menace to enemy submarines would be created if, in addition to fast surface escort vessels, a really very strong force of bombers and escorting FAA aircraft were organized to attack the submarines at very low level and harry them continually.

Also that the enemy submarines, even if provided with extra platforms, could not each carry on their small superstructure the large number of machine-guns and 20-mm and 40-mm cannon-guns which each of our merchant ships mounted, in addition to a 4-inch or 12-pounder AA gun.

So the submarines would not often triumph by gunfire as our merchant ships did against low-level bomber attacks. In 1941 Allied merchant shipping had been sunk by low-level bomber attacks at a rate of 3.5 million tons per annum until we taught them how to shoot the bombers down. This reduced in a few months the rate of sinking by bombers to 0.25 million tons per annum. (I had called attention to the vital importance of building large numbers of fast, ocean-going escort vessels before the war, in a letter published by the Daily Telegraph of the 1st of February 1937, under the heading: “The Merchant Service’s Need: Neglected Branch of our Defences.” Large numbers of these craft were under construction in 1942).

It chanced that my suggestions were well timed, as they would put into effect conclusions reached just afterwards by the Casablanca Conference (of which I knew nothing), which met from the 14th to the 25th of January 1943, and – as announced to the House of Commons on the 11th of February of the same year – that Conference laid emphasis on the necessity for defeating the submarine menace.

Canadian, American and more RAF Long-Range Bombers cover Shipping

Action was taken in March 1943. Canadian and American long-range bombers for Merchant Navy cover were based in Newfoundland and associated with our Coastal Command. (The USA were able to give this help because they had mastered by mid-1942 the serious attacks by submarines in the Caribbean and off the east coast of North America). Our Coastal Command was also strengthened by more bombers from our Bomber Command and from the American long-range bomber forces in the British Isles. Extra fuel tanks were added to aircraft where necessary to increase the range of action. Very long-range Coastal Command bombers were established, inter alia, on the air station in Iceland, and, later in 1943, in the Azores and further south. ‘The gap’ in mid-Atlantic, some 600 miles wide, which had been left unprotected by the shore-based aircraft in 1942, was now covered by them as well as by escort-carrier aircraft and MAC [merchant aircraft carrier] aircraft.

Increased sea and air attacks were organized in the Bay of Biscay against enemy submarines operating from French Atlantic ports. The effect of these arrangements was immediate, the enemy submarines being defeated in a few months.

In 1943 shore-based aircraft sank 116 German submarines, i.e., 80 more than in 1942, the next best being by ships 59, and by ship-borne aircraft 24.

To put it in a nutshell: The Battle of the Atlantic was won in 1943, thanks largely to the unbreakable courage of our merchant seamen, whose ships also carried seamen gunners of the Royal Navy and men of the maritime regiment of the Royal Artillery. The protection given them was enormously strengthened in 1943 by the large increase in Allied long-range bomber cover mentioned above, and FAA and US naval aircraft flying on and off escort carriers and merchant aircraft carriers in all weathers – also by increased numbers of fast ocean-going escort vessels.

In bringing troops and vital food and war supplies to us and our Allies throughout the 1939-45 war, 30,189 officers and men of the Merchant Navy were killed with 5,264 missing. The killed included 21 commodores of ocean convoys (12 retired admirals, one captain RN, one captain RIN, and seven captains RNR).

War cannot be waged without some mistakes, but nothing can dim the splendour of Mr. Churchill’s achievement.

Postscript to Members of The Naval Review

I wrote the above article for the Commonwealth and Empire Review in order to call the attention of the public to:

(a) The enormous importance of the Merchant Navy.

(b) The fact that it is easy for the Navy, Army and Royal Air Force to work together, as they enjoy mutual affection and respect; but, while it is of the utmost importance for them to co-operate to the closest extent, care must be taken that special weight is given to the opinions of sailors on operations at sea. (The call for a reinforcement of hundreds of bombers operating from increased numbers of shore stations to save the Merchant Navy in 1943 – came from the sea. That recalls the great Duke of Marlborough’s remark quoted above in my article).

It often happens in war that large scale operations are undertaken although it is realized that these are at the expense of less important operations. Decisions to do this are made on the highest level of Control and Command. It is there that relative weights are given to the various claims for forces, equipment, shipping, etc.

Let us agree with Marshal Turenne that: “He who has made no mistakes in war has never made war.”

We are immensely grateful to all the Allied leaders for bringing about the victorious end of the war on a gigantic scale in both hemispheres. Outstanding is the figure of our great war leader, Mr. Churchill, the splendour of whose achievements will be remembered through the centuries. He gave inspiration to our people.

It is not a mark of ingratitude to search for better solutions of problems dealt with. It is, in fact, an important duty of the moment, in order to arrive at the best solutions to meet our defence requirements in the future.

This article emphasizes the tremendous task involved in the defence of our Jugular Vein – the Merchant Navy – in war. Its readers among the public should realize – as the Navy does – how we and our Allies held the command of the sea and that this enabled the Merchant Navy convoys to plough the Seven Seas in the face of violent and continuous enemy attacks. (The Japanese gained command of the Pacific by the Pearl Harbor treachery; but they lost it as the result of smashing blows from the navies of the USA, Britain and their other Allies; and with the loss of command of the sea the Japanese lost the war).

In 1943-45 each convoy had its swarm of fast ocean-going escort vessels, and an escort aircraft carrier or MAC, and in the Atlantic also had Coastal long-range aircraft patrolling overhead. Independent hunting squadrons of fast escort vessels including carriers and also of Coastal aircraft operated in various areas against enemy submarines, especially in the Bay of Biscay.

It has been stated in the Press that we developed centimetric wave Radar (in thesummer of 1942) which increased the range at which an aircraft could expect to pick up a submarine on the surface from three or four to eight or nine miles. This also made it difficult for an enemy submarine to become aware that Radar observations were being made on it. Radar shows on its screen the positions of vessels on the surface and aircraft within its range. The Leigh searchlight in aircraft was valuable at short range. The asdics in escorting vessels probed all round under water for enemy submarines.

Of the 781 German submarines destroyed, 525 were accounted for by British Empire forces and other Allied (except USA) forces under British Operational Control. 174 were accounted for by American, i.e., all US and Allied (other than British, Dominion and Imperial) forces under US Operational Control. 82 from other causes.

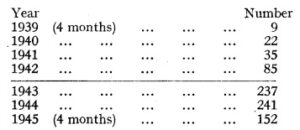

It is of interest to note that the 781 German submarines were sunk in the following years:

Readers should also have in mind the vital cover given by battleships, cruisers, fleet carriers and destroyers suitably disposed. To quote a few examples in the Atlantic, Arctic and Pacific Oceans and in the Mediterranean:

- The German battleships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau stood down south to attack a convoy off West Africa; but, when HM battleship Malaya emerged from the convoy to do battle, they fled north-west right across the Atlantic and attacked shipping off Newfoundland; finding HM battleship Rodney there, they bolted to Brest.

- The German battleships Graf Spee (South Atlantic), Bismarck (North Atlantic) and Scharnhorst (Arctic) when attacking or menacing our trade were destroyed by HM ships, the two latter by battleships. (The Bismarck was pulled up by FAA carrier-borne aircraft in a heavy seaway).

- The German battleship Tirpitz, in Norway to attack our Arctic convoys, was immobilized in harbour by Fleet Air Arm carrier-borne aircraft and midget submarines until sunk at anchor by RAF planes.

- The German 8-inch gunned cruiser Prince Eugen stood out from Brest and attacked a convoy, but was driven back to harbour, with severe casualties and her Admiral killed, by the escorting 8-inch gunned cruiser HMS Berwick.

- The Italian Fleet was hamstrung at Taranto by the Fleet Air Arm carrier-borne aircraft. Three heavy Italian cruisers were sunk by our battleships in the Battle of Cape Matapan, after having been located and damaged by FAA carrier-borne aircraft.

- Our heroic convoys to Malta were covered by ‘H’ Force of battleships, carriers, cruisers and destroyers. Our carriers flew off RAF Spitfires into Malta. Thus aircraft carriers saved Malta.

- In all seas the landings were covered by battleships, aircraft carriers, cruisers, destroyers, submarines, etc. Also when possible by land-based aircraft.

- The growth of the US Navy was gigantic in the period between December 1941 (Pearl Harbor), and the signing of the Japanese surrender on the 2nd of September 1945. The US naval personnel increased from 150,000 to 3,315,000, with complete training arrangements (in the First World War the Royal Navy increased to some 450,000). An enormous naval shipbuilding programme of fully-equipped and highly efficient vessels, including large numbers of aircraft carriers and more than 22,000 naval combat aircraft, was carried out at great speed. Full provision of advanced repair and supply bases was made. The US and British submarines and carrier and land-borne aircraft did enormous damage to enemy men-of-war and shipping. The Japanese were utterly crushed at sea.

- In the Battle of Leyte in the Philippines the US battle fleet played an essential part in driving back the attack of the Japanese battle fleet on the US landing armada.

We and our Allies were able to win both the World Wars at sea largely because of:

- The fortitude, skill and seamanlike ability of our sailors – Navy, Merchant Navy, fishermen, yachtsmen and new sailors.

- The enormous shipping output of the USA.

German submarines were continuing to reduce the available total of Allied tonnage until the end of 1942. In the two years 1943 and 1944 the USA shipyards averaged one million tons production per month; i.e., 24 million tons of merchant ships for the two years. British shipyards totalled four million tons production for those two years.

In the Second World War aircraft played an increasingly important part, sailors flying on and off fleet and escort carriers and MACs in all weathers. Large shore-based aircraft were of enormous importance over sea routes they could reach.

The British Isles were the foremost bastion (against Germany) with the Jugular Vein to all parts of the British Empire and the USA and other countries.

Throughout both World Wars the convoys stood bravely on and maintained formation and maneuvering power in the face of nearly every form of attack.

Terrible atomic and other weapons of war may be produced; and we must plan and thoroughly arrange to meet such menace to our Jugular Vein in any future war which may break out. In peace time the British Merchant Navy carries over 100 million tons of cargo per annum.

The Merchant Navy must be held in high honour and have plenty of fine ships, and thorough provision must be made for their welfare.