What is to Be Done? How China is Responding to Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine

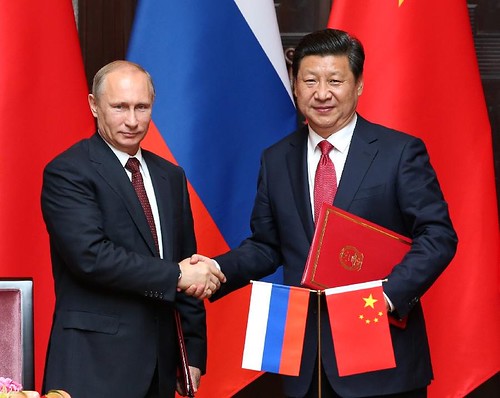

By the Editor – At the opening of the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics, President Putin declared: “friendship between the two states [Russia and China] with no limits, no forbidden areas of cooperation.” The author explores how realpolitik might be refocussing the PRC’s mind following Putin’s invasion of Ukraine.

Having first been asked to write this article shortly after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, my impression on the likely geopolitical consequences was very different (and much more pessimistic) than it is now, just a few weeks later. I had been convinced that Russia would invade Ukraine, but my expectation was that the invasion would be overwhelming, and the West’s response would be largely ineffectual, thus enabling Putin to act with impunity. I believed that this, in turn, would embolden other autocracies like China to capitalise on the West’s division and distraction to fulfil its grand strategic goals.

The events of the last few weeks (from Russia’s mystifyingly poorly organised invasion, to President Zelenskyy’s outstanding global diplomacy, to the West’s surprisingly robust response), have radically changed the narrative. I would argue that Vladimir Putin is a good candidate for Time Person of the Year 2022, for having done more than anyone else to unite the West and strengthen Europe’s resolve for collective defence.

I am conscious that given the rate at which events are moving, by the time this piece has been published, the situation will have changed still further. With that in mind, this piece represents my assessment of the broader geopolitical implications of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, particularly its implications for China, as of mid-March 2022.

The World’s Response to Russia

Whilst few would doubt that the world has changed, fewer still could claim to understand exactly the long-term implications of this change. What is clear, however, is that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine will have implications far beyond Eastern Europe.

Whilst there has been a surprising degree of unanimity in the international community, a closer inspection reveals fault lines. Sanctions have largely originated from NATO and EU countries plus others in the Asia Pacific region such as Australia, New Zealand, Japan, and South Korea. Much of the Global South, including most countries in South America and Africa, have thus far avoided serious engagement. Even India has remained neutral, attempting to balance its strategic partnership with the ‘Quad’ against its traditional relationship with Russia. The most impactful country though, and the one who will have the greatest influence over the future structure of the international system, is the People’s Republic of China.

China’s Relationship with Russia

Despite a shared commitment to Communism during the Cold War and authoritarianism now, China’s relationship with Russia is a complex one – defined as much by geography, demography, and personality, as by ideology.

In the years after the Second World War, Mao Zedong’s PRC was very much a junior partner to Stalin’s USSR. Over the decades, however, paranoia and realpolitik led to a more strained relationship, culminating in the seismic geopolitical realignment of China’s rapprochement with the US in 1972.[i] With the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 the PRC was the only major ‘Communist’ power left on the world stage (albeit increasingly Communist in name only). Since then, China has overtaken Russia economically and politically, rapidly taking up the mantle of superpower whilst its erstwhile big brother languished in chaos and corruption.

Over the last decade, however, worsening relationships with the West and increasingly autocratic tendencies have brought the two closer together than at any point since the beginning of the Cold War. Analysts have warned of this ‘alliance of autocracies’, going as far as to suggest that the West should attempt to divide the two by attempting a ‘reverse Kissinger’ to entice Russia away from China and towards the West.[ii]

Despite having once been a global superpower, Russia’s international influence is not commensurate with its size. Russia is the largest country in the world and the has largest natural gas reserves in the world.[iii] However, decades of corruption, as well as economic sanctions, have stunted its economy.[iv],[v] Russia’s GDP per capita in 2021 was just $10,126 in comparison to China’s $12,554, despite China having a population that is literally ten times larger.[vi],[vii],[viii] In an inversion of the Cold War Soviet dynamic, China is now the senior and Russia the junior partner. Russian businesses and politicians have found that Beijing drives a hard bargain however, relentlessly using its superior economic and political position to entrench advantage on its terms.[ix]

China’s Response to the Invasion

China has thus far avoided taking a definitive side in the conflict, including abstaining from UN Security Council and General Assembly votes.[x],[xi] Beijing has carefully stage-managed its public response, at no point publicly acknowledging it as an invasion, whilst using state propaganda to support Russian narratives around the war. The People’s Daily (the CCP’s official newspaper) posted videos of Russia providing humanitarian aid to Ukrainians in Kharkiv, whilst Beijing has amplified Russian disinformation about bioweapons in Ukraine, calling for a UN investigation.[xii],[xiii] In an embarrassing lapse, a senior editor at Xinhua News Agency accidentally posted its own censorship stance on Weibo, stating that it would only publish pro-Russia content. They also noted that China needed to support Russia now since China would also need Russia’s understanding and support when wrestling with America to “solve the Taiwan issue once and for all.”[xiv] Unsurprisingly, the post was almost immediately deleted.

Whilst China lacks the West’s open public discourse, there are some signs of dissent within policy-making circles. On the 12 March, Hu Wei, a senior Chinese academic and public policy expert, published an article analysing the Russian invasion and exploring its implications in the international arena.[xv] In it, he assessed the conflict would help unite the West, shoring up the US’s leadership in the world and bolstering NATO. He also predicted that China would become more isolated under this re-established framework. He warned that China must not be tied to Putin and that “China should rejoice with and even support Putin, but only if Russia does not fail.”

Most explosively, Wei proposed that: “China should avoid playing both sides, give up being neutral, and choose the mainstream position in the world. Given that China has always advocated respect for national sovereignty and territorial integrity, it can avoid further isolation only by standing with the majority of the countries in the world. This position is also conducive to the settlement of the Taiwan issue.”

Wei further noted that “cutting off from Putin and giving up neutrality will help build China’s international image and ease its relations with the US and the West”. Such a forthright opinion is rare from within China’s establishment – particularly one that doesn’t toe the party line. The article was widely shared on Chinese social media, achieving more than one million views before it was censored.

Another Chinese policy expert later posted a rebuttal, noting that “the article [is] very unflattering, neither in line with mainstream domestic public opinion, nor in line with top-level direction.”[xvi] Whilst intriguing to see, the swift response in censorship, as well as Beijing’s actions so far, would suggest that there is little appetite as yet to completely cut ties with Russia.

As the war has dragged on however, there have been signs that Beijing is increasingly unhappy with the situation and concerned with the potential risks of escalation. At a virtual summit with the leaders of France and Germany on 8 March, Xi Jingping was quoted as saying: “…the Chinese side is deeply grieved by the outbreak of war again on the European continent […] the sovereignty and territorial integrity of all countries must be respected, the purposes and principles of the UN Charter must be fully observed, the legitimate security concerns of all countries must be taken seriously, and all efforts that are conducive to the peaceful settlement of the crisis must be supported. The pressing task at the moment is to prevent the tense situation from escalating or even running out of control.”[xvii]

Whilst still clearly hedging their position (China has long used “legitimate security concerns” to criticise NATO’s posture), this is the most unequivocal signal yet that China is unhappy with the war in Ukraine.

China & Taiwan

While they would never acknowledge it publicly, the comparisons between Ukraine and Taiwan will not have been lost on Beijing. Taiwan has been a de facto independent state since the foundation of the PRC in 1949. Since 1996, China has pursued an influence campaign to improve cross-strait relations with the long-term intent of peacefully unifying the two states.[xviii] Beijing has focused on improving economic and cultural ties and showing support for Taiwan’s interests.[xix] One of Xi Jingping’s fundamental goals is to have achieved “national rejuvenation” by 2049 (the 100th anniversary of the PRC).[xx]

In recent years, however, Beijing’s strategy in Taiwan has been undermined by its tactics in Hong Kong. Its willingness to renege on Hong Kong’s ‘one country, two systems’ (agreed under the Sino-British Joint Declaration), has led to a collapse of support for reunification in Taiwan since 2018. [xxi],[xxii] This violation of the status quo in Hong Kong has undermined decades of soft power strategy in Taiwan, fatally undermining its strategy for peaceful cross-strait reconciliation.

As prospects of peaceful reunification between the PRC and Taiwan have become more remote, the likelihood has increased that Beijing would attempt a forceful reunification of the island. It has significantly stepped up its military incursions into Taiwanese airspace, entering the island’s ADIZ (Air Defence Identification Zone) on a record 91 days between January and November 2020, applying pressure to the Taiwanese government and signalling to the West its resolve.[xxiii]

How Does This Affect China?

In terms of both military and political strategy, China will have been watching the invasion of Ukraine closely. Whilst Beijing has in recent years gone to great expense to modernise the PLA Army, Navy, Air Force, and Rocket Force, so (officially) had Russia. However, this turned out to be a mirage, crippled both by rampant corruption and a uniquely authoritarian blindness to bad news (nobody wants to tell the boss that his armed forces are in a terrible state if it means explaining to him where all the money has really been going over the years).

Politically, Beijing will have also been dismayed by the unanimity and force of the West’s response to Russia’s invasion. The United States has long pursued a policy of ‘strategic ambiguity’ toward Taiwan, refusing to explicitly state whether it would come to the island’s aid in the event of an invasion. The forceful response to Russia’s invasion, as well as the radical shift in many European nations’ defence posture, will have undercut any notions of the West’s withdrawal and likely shifted Beijing’s assessment of the likelihood of a hard-line response to a future invasion of Taiwan.

That said, despite searing economic and financial sanctions, the West has been unwilling to directly intervene militarily, largely due to concerns about the prospect of an all-out war between NATO and Russia. China may conclude that not only will the West be just as reticent to commit to a military intervention in support of Taiwan, but that it will also be far less willing to sanction China, the second largest economy in the world.

Nevertheless, Beijing will no doubt be carefully assessing how international sanctions crippled Russia’s once-vaunted “war chest”, some $600 billion in reserves that were intended to prop up the economy in the event of international sanctions.[xxiv] This turned out to not quite be the formidable bulwark expected, when it transpired that $300 billion of it was held as foreign exchange reserves in Western banks – all of which was promptly frozen.

The nuclear bomb in the arsenal of economic sanctions has been the removal of several Russian banks from SWIFT (the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication) – SWIFT is the global financial infrastructure that underpins the majority of financial transactions in the modern world.[xxv] It is hard to overstate just how fundamental SWIFT is to the international financial system (imagine if the RN at a stroke lost all electronic communications and had to resort to carrier pigeon instead). Removal from SWIFT effectively means banishment from the modern financial world – it doesn’t matter if you have $600 billion in reserves if you can’t transmit the money to your debtors.

While a devastating weapon in its arsenal of financial weapons, the US has long been reticent to pull the trigger. Over the last decade, China has made huge investments in building an alternative infrastructure to challenge the US’s economic hegemony, promoting the Renminbi as an alternative global reserve currency to the Dollar and developing the Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS). Whilst SWIFT’s position in the global financial system is overwhelming, it is not absolute. Excessive use of SWIFT as a cudgel in financial sanctions could encourage a critical mass of countries to look for an alternative system such as CIPS, thus accelerating the decline of the Dollar as the primary global reserve currency. Whilst Beijing will no doubt be concerned about the effectiveness of Western sanctions against Russia, it will also be carefully considering the potential strategic opportunities.

Despite the longer-term opportunities such a rupture might provide China, the world’s economic centre of gravity still lies with the US. Regardless of what position the government takes regarding Russia, Chinese businesses and banks are already voting with their feet. Under the threat of secondary sanctions (that is, the threat of being sanctioned for continuing to trade with a sanctioned entity), several of China’s largest state-owned banks have already restricted financing for purchases of Russian commodities.[xxvi] Beijing may publicly state that it will continue to trade with Russia, but there is a significant difference between Beijing being willing to trade versus actively forcing Chinese entities to continue trading with Russia.

So the conflict in Ukraine (at least in as much as it has played out so far) is not good for China. It leaves it in an intensely awkward situation, stuck between its longstanding public position that external countries should not interfere in the internal matters of other states (it sees no contradiction between this and the Taiwan issue, regarding Taiwan as a ‘renegade province’, rather than an independent state) and its close relationship with Moscow.

What are China’s Difficulties?

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has trapped Beijing between conflicting political principles. China has consciously been developing a relationship with Russia that represents an authoritarian alternative axis to the US-led Liberal hegemony. In this they have used a range of tools, including supporting each other in vetoing/voting down objectionable initiatives in the UN General Assembly and UN Security Council, as well as opportunistically using rhetoric to undermine the West.

China, despite sharing Russia’s revanchist attitude to the international system, calculates that it has more to gain from embracing international frameworks than from undermining them. Russia appears to have a more nihilistic strategy, calculating that it is easier to undermine the existing international system than it is to co-opt it.

In its attempts to adjust the international system in its favour, China has long preached a ‘sovereigntist’ philosophy, arguing that a nation’s right to self-determination is inviolable. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine directly contradicts that principle (hence why domestic media is playing down discussion of it as a war at all). Beijing is thus caught between sustaining the anti-West axis it has been developing in recent years versus undermining the sovereigntist principles it champions on the world stage.

What Will China Do Next?

Above all, China’s political priority is to make the conflict go away. The war is doing a spectacular job of uniting the West in ways no one would have anticipated even a month ago. The longer this goes on, the worse it will get. It has almost single-handedly revitalised NATO and European security consciousness. As Hu Wei observed, this is a disaster for China.

This conflict, and the West’s surprisingly robust response to it, will have given Beijing pause for thought when it comes to Taiwan. A forcible reunion between mainland China and Taiwan is now less likely, at least in the near-medium term future (12-24 months).

China will seek to avoid being too associated with Russia, without fully repudiating their ally. This can be seen in their efforts to hedge their bets on the international stage and heavily censor information about the war domestically. Despite the difficulty of the situation, Beijing will still seek opportunity in the rough. It will continue to amplify Russian narratives about the threat of the West and NATO, amplify disinformation and use this conflict to stoke nationalism at home.

Although it has reportedly been approached by Russia, China is also unlikely to directly provide weapons in support of the invasion.[xxvii] Whilst it may provide some limited secondary support, Beijing will be reticent to be directly associated with such a bloody conflict. Beijing will likely increasingly look to apply quiet diplomatic pressure to Russia to bring the conflict to a conclusion.

Assuming that Putin isn’t the victim of a coup or ‘unfortunate accident’ in the near future, the sanctions levied by the West are unlikely to be relaxed even if the conflict concludes with a ceasefire or stalemate. Although individual Chinese banks and businesses may choose to avoid engaging with Russia for fear of secondary sanctions, Beijing itself will not cut Russia off. Whilst it does not want to be publicly associated with Russia’s misadventures, China will likely capitalise on Russia’s newfound economic isolation to entrench its position as partner of last resort. Absent any other changes, it will likely impose a similar dynamic to its relationship with North Korea – acting as the only major economic power willing to trade with them, for a price. Russia will find that Chinese charity in short supply however, suffering from the imposition of heavy premiums in return for their willingness to trade.

Most importantly for China’s long-term economic position, Beijing will look to capitalise on the sanctions package by pushing its alternative to SWIFT, positioning it as the system of choice for autocrats and non-aligned countries concerned about American financial hegemony. In the long term, fracturing the world’s reliance on the Dollar as the currency reserve of choice would have cataclysmic effects on the US’ economic power and influence on the world stage.

Conclusions

Vladimir Lenin (apocryphally) said that “there are decades where nothing happens, and there are weeks where decades happen.” The last few weeks have exemplified this truism as analysts the world over have scrambled to assess the seismic political shifts occurring as a consequence of Russia’s misjudged invasion of Ukraine. As I acknowledged at the beginning of this essay, in the time between being asked to write this article and actually completing it, my opinion has changed significantly. I am fully prepared for the risk that in the time between my completing this essay and it being published, it may have changed once again.

Just as military and political strategists in the West have struggled to guess as the consequences of the dizzying changes being wrought before us, our counterparts in China will be similarly confounded. The ferocity and unanimity of the West’s response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, as well as the shocking failure of both Russia’s military campaign and its economic protective measures, will have left China’s politicians, economists, and military strategists scrambling to understand the implications for themselves.

[i] https://history.state.gov/milestones/1969-1976/rapprochement-china

[ii] https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2021-08-04/right-way-split-china-and-russia

[iii] https://www.cia.gov/ the-world-factbook/field/area/country-comparison

[iv] FPRI, 2018. Corruption and Power in Russia – Russia Political Economy Project. Foreign Policy Research Institute.

[v] Korhonen, L., 2019. Economic Sanctions on Russia and Their Effects. Leibniz Information Centre for Economics.

[vi] https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2010/07/16/foreign-direct-investment-china-story

[vii] https://www.ceicdata.com/en/indicator/china/gdp-per-capita

[viii] https://countryeconomy.com/countries/compare/china/russia?sc=XE23

[ix] https://ecfr.eu/publication/its-complicated-russias-tricky-relationship-with-china/

[x] https://www.reuters.com/world/russia-vetoes-un-security-action-ukraine-china-abstains-2022-02-25/

[xi] https://www.scmp.com/news/china/article/3169010/un-votes-condemn-russian-invasion-ukraine-china-again-stays-silent

[xii] https://www.rferl.org/a/china-echoes-russia-ukraine-war/31745136.html

[xiii] https://www.un.org/press/en/2022/sc14835.doc.htm

[xiv]https://www.businessinsider.com/china-news-outlet-ukraine-coverage-instructions-weibo-horizon-russia-2022-2?r=

US&IR=T

[xv] https://uscnpm.org/2022/03/12/hu-wei-russia-ukraine-war-china-choice/

[xvi] https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/WCcXCEGZdsqL30VvZ1MCaA

[xvii] http://www.chinaembassy.or.th/eng/zgyw/202203/t20220308_10649839.htm

[xviii] Joseph, W., 2019. Politics in China: An Introduction. 3rd ed. Oxford University Press.

[xix] Kalimuddin, M. and Anderson D. A., 2018. ‘Soft Power in China’s Security Strategy’, Strategic Studies Quarterly. 12(3), pp.114-141

[xx] https://www.cfr.org/blog/what-xi-jinpings-major-speech-means-taiwan

[xxi] https://ash.harvard.edu/files/ash/files/overholt_hong_kong_paper_final.pdf

[xxii]https://esc.nccu.edu.tw/ PageDoc/Detail?fid=7801&id=6963

[xxiii] https://www.scmp.com/news/china/military/article/3116557/pla-warplanes-made-record-380-incursions-taiwans-airspace-2020

[xxiv] https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/russia-ukraine-sanctions-b2023198.html

[xxv] https://www.investopedia.com/articles/personal-finance/050515/how-swift-system-works.asp

[xxvi] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-02-25/chinese-state-banks-restrict-financing-for-russian-commodities

[xxvii] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/mar/14/us-will-try-to-convince-china-not-to-supply-arms-to-russia-at-key-rome-meeting